Calyx Global has assessed over 70 REDD projects, including taking a close look – using a range of geospatial data and methodological approaches – to assess whether the project was overestimating its baseline. An overestimated baseline, i.e. the assumed amount of forest loss that would occur in the absence of the project, is the key factor in determining the amount of claimed emission reductions from REDD projects. Those claims are then utilized by companies and organizations to make their own offset or contribution claims.

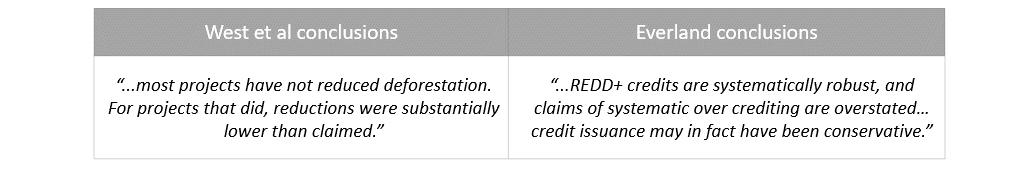

So, why did the Everland study come to such different conclusions?

#1 - Faulty assumptions

The Everland report makes the following assertion to back its claims that REDD baselines are robust:

“REDD+ baseline predictions closely match actual observed forest loss. Overall, predicted REDD+ baseline forest loss rates across 7 countries correspond remarkably closely with the actual forest loss that took place in the jurisdictions surrounding REDD+ projects.”

The comparison of forest loss rates in a jurisdiction to those in project areas can be an interesting analysis. However, it is not a reasonable way to assess the counterfactual baseline, i.e. “how much deforestation would occur in a particular area” without the REDD project.

The Everland study assumes that projects are located, on average, in areas that are representative of the entire jurisdiction when it comes to the risk of deforestation. But this is actually not the case. Often, projects are selecting parcels of forest land that are not as threatened as those throughout the jurisdiction. In the case of forest-based carbon projects, things like rivers, roads and private ownership can drive dramatically different deforestation rates across a single jurisdiction. Indeed, part of the motivation for conserving these areas is that they are still relatively intact. The accompanying Perspective in Science makes the same point – namely that there is a “tendency to locate projects in areas with low background deforestation”, further noting that this “makes REDD+ projects appear more successful at reducing deforestation than they were”.

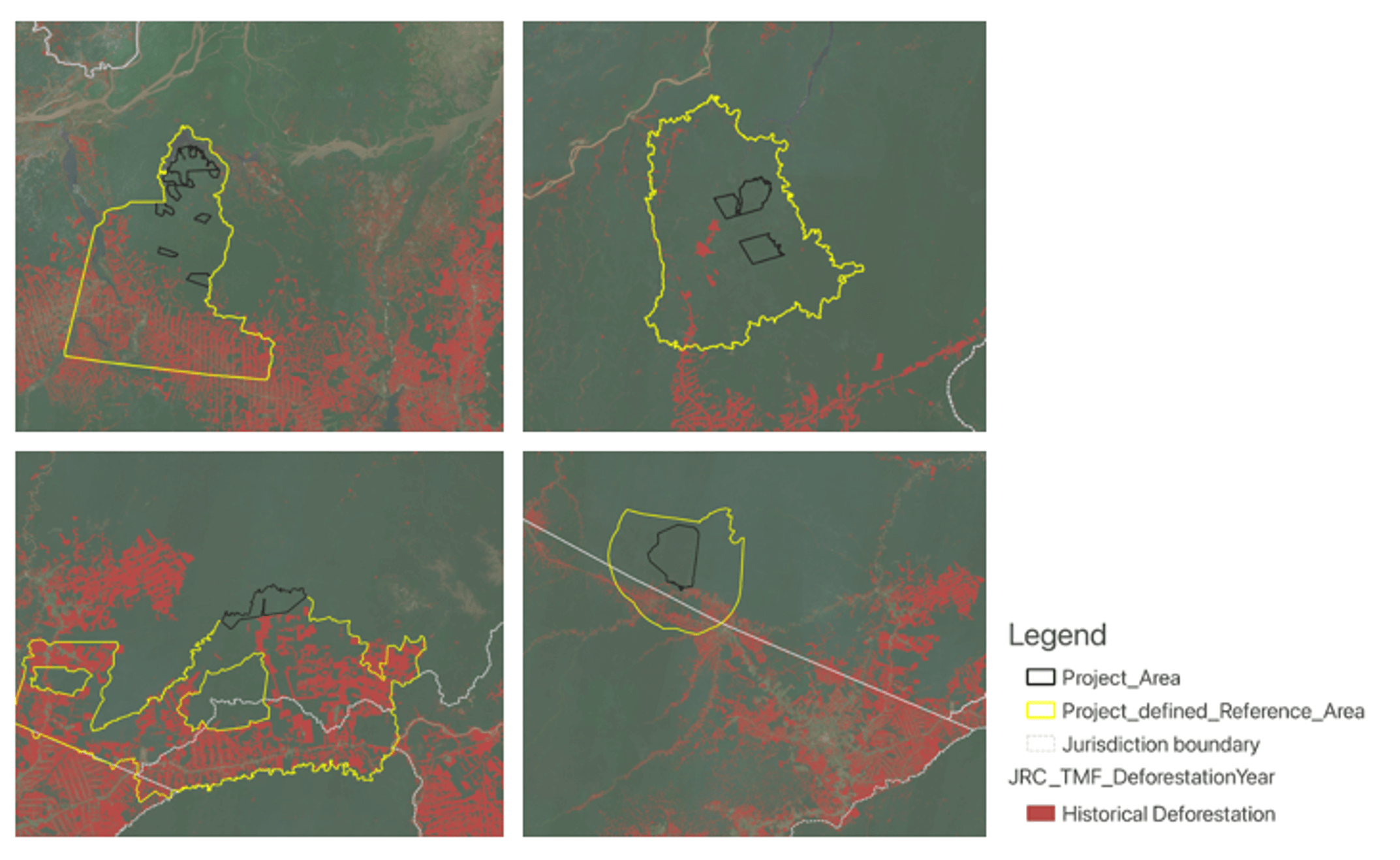

The images below of four REDD projects illustrate this issue. One can see that the project areas (black outlines) do not experience forest loss (red pixels) comparable to those of the broader region. The fact that project baselines ‘match’ jurisdictional loss rates is not a happy coincidence. Rather, it is a result of projects including in their self-selected reference regions (yellow outlines) areas with higher historical rates of deforestation, rates at or above the level observed across the jurisdiction.

The critical issue, unaddressed in the Everland study, is what was happening in and near the project area before the project started, and what is likely to happen in the near future? It can be inaccurate to simply look at broad deforestation rates and not account for behavior on a particular parcel of land. Comparing the average deforestation rate across all jurisdictions with the average deforestation rate implied by all baselines and the average observed deforestation rates in the projects is not a rigorous analysis. While we question the comparison against jurisdictional data, we would also argue for a more robust statistical approach that matches an individual project with its own baseline that reflects the forest dynamics in nearby areas with similar land use and expected deforestation drivers.

#2 - Drawing the wrong conclusions

While the analysis may or may not be correct, i.e. that REDD baselines match, on average, the jurisdictional deforestation rates, the conclusion is not a given. Everland states the following:

“REDD+ projects are effective. Forest loss in 53 REDD+ project areas was more than a factor 10 lower than either their baselines, or the actual forest loss which took place within their surrounding jurisdictions.”

It is very hard to make this assertion from the analysis provided. As one can see from the figures above, one would expect forest loss to be lower in the project area compared to the regional average loss. One cannot draw a conclusion about the effectiveness of the project without a better estimation of what the forest loss rate would be in the absence of each project.

#3 - Blaming the wrong actor

Everland points to studies, such as the one from Science, as creating an unwanted result:

“the impact has been to stop the flow of funding to some of the world’s most disenfranchised forest communities who struggle to meet basic needs, and who for the first time have had a viable alternative to meeting those needs by conserving – instead of converting – some of the world’s most threatened forests.”

This would seem to suggest that the authors of the Science article, and others who call out the current situation with regard to overestimating emission reductions from REDD projects are somehow responsible for stemming the flow of finance to forest communities.

At Calyx Global, we agree with the authors of the Science article, who clearly state that methodologies used to construct deforestation baselines need urgent revisions. Bringing science to our understanding of credit quality is critical to meeting our climate goals. Furthermore, if buyers are using credits to offset their emissions, then we cannot turn a blind eye to the real emission reduction impact that carbon projects are making.

As the ICVCM has stated: “Build integrity and scale will follow.” We believe that this is the case for REDD – that to drive sustainable finance through carbon markets to protect forests and to benefit forest-dependent communities means we can no longer afford to be in denial of the problems, but that we must first confront them and together find solutions.

Read more about our analysis in Turning REDD into Green.

Get the latest delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our newsletter for the Calyx News and Insights updates.